dr.francesco pensato

Symbolisms: Part Two

Historical-Esoteric Interpretation of Symbolism in the Art of Leonardo da Vinci

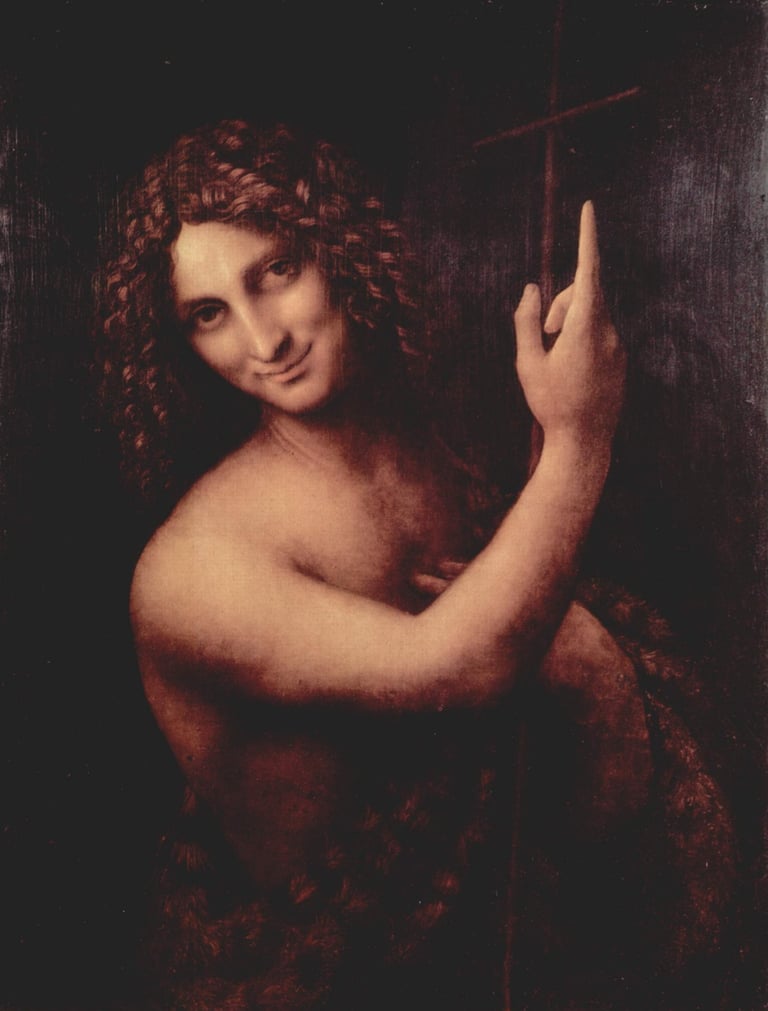

The Finger of God

In many of Leonardo’s masterpieces—and not only his—the symbol of the index finger pointing upward frequently recurs, deeply rooted in the Mandean or Johannite tradition.

This esoteric message is undeniably linked to the artist’s affiliation with a secret esoteric movement, to which several Renaissance figures, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, belonged.

The first appearance of this gesture in Leonardo's works is in The Adoration of the Magi, an oil painting on wood from 1481, measuring 246 x 243 cm, exhibited at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

This is perhaps the most significant work of his Florentine period, where every figure participates with their emotions in the depicted scene.

Commissioned by the monks of Scopeto as an altarpiece for their convent, the unfinished work was eventually replaced by a painting of the same subject by Filippino Lippi. In 1482, Leonardo left Florence for Milan, abandoning the project in its preliminary stages.

Yet even in this sketch, key aspects of Leonardo’s style can be identified, such as his attention to the mechanics and anatomy of figures and his study of bodies in space.

Some scholars have identified the young man at the bottom right, turned outward, as a self-portrait of the young Leonardo.

In this painting, the gesture is directed toward the carob tree, sacred to John the Baptist, indicating, according to Mandean tradition, that the visit of the Magi (or Magicians) was meant for John the Baptist, not Jesus.

The same gesture appears again in the famous painting The Virgin of the Rocks.

The Virgin of the Rocks

On April 25, 1483, Bartolomeo Scorione, prior of the Milanese Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception (a lay male brotherhood), signed a contract with the young Leonardo, who had arrived in Milan about a year earlier. The contract was for an altarpiece for the chapel in the Church of San Francesco Grande (now destroyed).

This commission was Leonardo’s first in Milan, where he had been received with lukewarm enthusiasm. Present at the contract signing were the renowned painter brothers Evangelista and Giovanni Ambrogio De Predis, who hosted Leonardo in their home near Porta Ticinese.

The detailed contract stipulated a triptych. The central panel was to feature the Madonna in a lavish "azure ultramarine brocade garment" with "her son," God the Father above, also in "a golden brocade robe," surrounded by a group of angels "in the Greek style" and two prophets.

On the lateral panels, the confraternity requested four angels—“one singing and the other playing music.”

The side panels, entrusted to the De Predis brothers, were to depict angels in glory, all for a fee of 800 imperial lire, to be paid in installments until February 1485. The wooden framework was assigned to Giacomo del Maiano.

It is unclear why Leonardo changed the subject of the central panel, opting instead for the legendary encounter between the young Jesus and John, as narrated in the Life of John according to Serapion and other texts on Christ’s childhood.

Neither God the Father nor the prophets or angels “in the Greek style” were painted. Only two musical angels were depicted by Ambrogio de Predis on the side panels, now housed at the National Gallery in London.

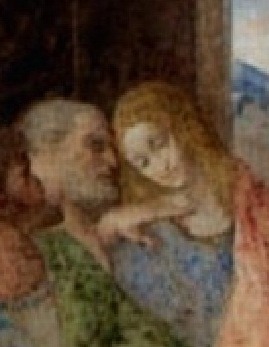

The first version, now in the Louvre, shows the child John beside the angel Uriel, who points a finger, like a weapon, toward the child Jesus while John is portrayed in the act of baptizing him.

This pictorial representation confirms that Leonardo was familiar with the apocryphal Gospels, particularly the Life of John, written in 390 CE by the Egyptian bishop Serapion, in which this scene is described as depicted in the painting.

Anomalies and Symbolic Proportions

Upon careful observation of the painting, a series of perspective anomalies stands out—an oddity for a genius always striving for meticulous perfection in details.

Leonardo himself immortalized such principles in his Vitruvian Man, where the study of proportions was a fundamental pursuit, embodying the Golden Ratio—the harmony and beauty inherent in nature.

A simple way to achieve the Golden Ratio is by using the Fibonacci sequence, a recurrent series of natural numbers where each term is the sum of the two preceding ones: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, and so on.

The ratio between two successive terms in this series approaches the Golden Ratio (approximately 0.618) as the sequence progresses. For example:

1:2 = 0.500

2:3 = 0.667

3:5 = 0.600

5:8 = 0.625

8:13 = 0.615

13:21 = 0.619

Conversely, reversing the factors (e.g., 55:34) yields approximately 1.6, another expression of this ratio.

Given the above, the presence of certain disproportions in The Virgin of the Rocks appears even more anomalous, suggesting that these were intentional and imbued with precise symbolic meaning.

Extreme length and disproportion of the right arm

Claw-like, predatory hands

Unusual abdominal drapery of the "Virgin"

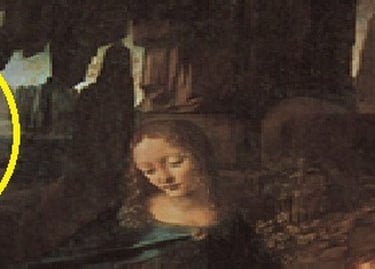

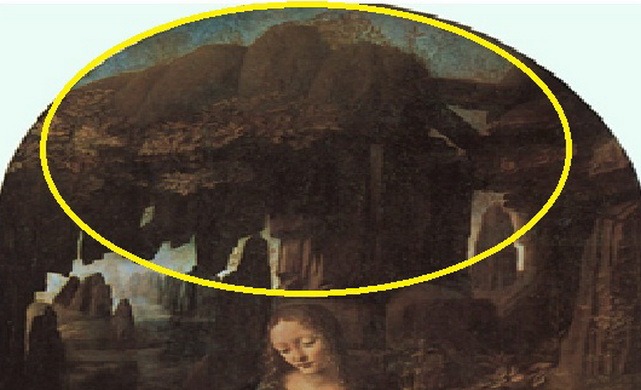

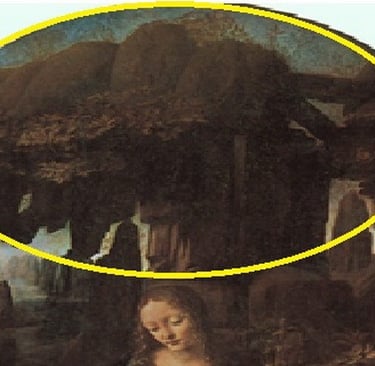

Background rock shaped like a hand

Upper cave shaped like a hand

The symbol of the finger

Finally, the sharp finger symbol and the Virgin's left hand, seemingly poised to grasp, have led to the hypothesis of a scene in which the finger symbolizes the weapon used to sever John the Baptist's head. This, in turn, could fit perfectly into the upper space between the sharp finger (symbolizing a cutting weapon) and the claw-like hand.

The Virgin's gaze, affectionate in demeanor, is directed at this point, while the enigmatic gaze of the angel Uriel is fixed outward, meeting the observer's eyes.

The finger, finally, points in the direction of Jesus, who is in the act of being blessed by John the Baptist, as is traditional.

Officially, according to various scholars—certainly "aligned" ones—Christ is identified as the infant figure on the right, not the left; that is, the one depicted in the act of giving the blessing. Consequently, John the Baptist would be the figure on the left, receiving it.

However, this description does not align with the apocryphal Gospel Life of John, written in 390 AD by the Egyptian bishop Serapion, which describes a scene where the angel Uriel, along with John the Baptist, meets the Virgin and the infant Jesus in that magical landscape.

We know with near certainty that Leonardo was aware of this Gospel, part of the historical and cultural heritage of the Neoplatonic Academy, which inherited Hermetic traditions.

There is also an interpretation, daringly proposed by some scholars.

In Orthodox historical tradition, it is said that John the Baptist was beheaded because of his preaching, in which he publicly condemned the behavior of Herod Antipas, who was cohabiting with his sister-in-law Herodias.

The king first imprisoned him, then, to please Herodias's beautiful daughter Salome, who had danced at a banquet, had him beheaded and brought her his head on a silver platter.

Without delving into the truth of the episode, it is worth noting that even in the canonical Gospels, the figure of Salome is often mentioned alongside Jesus.

Certainly, this could be a simple coincidence of names. But if it were not—if it were the same person—possible scenarios arise that could explain the marked hostility and evident aversion in Johannine writings toward Jesus Christ.

It could therefore be hypothesized that Jesus, with the help of his friend Salome, had "removed" from the scene someone with whom he would have legitimately shared power and leadership over the tribes of Israel, thus claiming both temporal and religious authority for himself.

In Essene tradition, there was a reference to the arrival of two Messiahs: the first, of temporal and political nature, belonging by right to the line of David; and the second, of religious nature, descended from the line of Aaron, a Levite.

Jesus undoubtedly belonged to the first lineage but, at the same time, through his maternal line, also to the Levitical one, as his mother was a cousin of Elizabeth, John the Baptist's mother. John, on the other hand, was a direct descendant of Aaron's line, being the son of Zechariah, the high priest of the Temple, and Elizabeth.

It is also interesting to highlight another strange coincidence. According to Johannine tradition, and also as reported by the historian Josephus in his numerous detailed accounts (Jewish Antiquities), the tragic event known as the "Massacre of the Innocents," carried out by Herod, did not occur because of the infant Jesus but because of the infant John—Herod sought to kill the Baptist.

Viewed in this light, the sharp finger, which like a weapon severs John's head, points toward Jesus, from a Uriel who looks at the observer with an unmistakable accusatory message.

There are two other versions of this painting:

One is kept in the National Gallery in London, and another belongs to a private Swiss collection, an exact copy of the Louvre's version.

In the London version, halos and John's cross-staff are present, but the gesture of the pointing finger is absent. It seems Leonardo adapted the work to meet the demands of the commissioner, in this case, the Franciscan Confraternity of the Church of San Francesco Grande in Milan.

In this version, many elements change, and many symbols inexplicably vanish.

The gaze of the angel Uriel is no longer directed outward but toward the child on the left, in whose arms the cross-staff is painted—absent in the original version—canonically identifying John the Baptist. Thus, Christ is no longer on the left but represented on the right, blessing.

Additionally, the rocks and cave shaped like a hand disappear. Halos are added to the children and the Virgin, absent in the first version.

The Virgin's hands are softer and less claw-like, but most striking is the absence of the "finger," obsessively depicted in multiple works.

Certainly, these changes were intended to please the commissioner. However, the subsequent question arises: did they fully or partially understand the symbolism to the point of requesting its removal?

The Last Supper

The Last Supper is a mural painting in tempera and oil on plaster, measuring 4.60 x 8.80 meters, created between 1494 and 1498.

Leonardo da Vinci received this commission from Ludovico il Moro, the Duke of Milan, who had chosen the Dominican church of Santa Maria delle Grazie as the ceremonial site for the Sforza family, funding significant restructuring and embellishment of the entire complex.

This magnificent work is still preserved in the former refectory of the convent, adjacent to the sanctuary of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

In this fresco, the focal image is represented by Christ at the center, flanked by distinct groups of diners.

The existence of an old copy dated 1735, created by an anonymous artist (possibly Cesare da Sesto), preserved in Ponte Capriasca, features the names of the Apostles identified at the bottom. Over time, this copy has influenced the attribution of the Apostles’ names in the original painting.

The Apostle to Christ's right is believed to be John, “the disciple whom He loved,” while the one to His left, with his index finger pointing upward, is identified as Thomas, the so-called twin brother of Jesus.

However, upon closer examination, the Apostle dressed in green to Christ’s left appears to bear a striking resemblance to Jesus and could likely be Thomas, while the figure pointing upward might instead be John the Baptist.

To Christ’s right, the position traditionally reserved for the most important Apostle, Peter, appears to be occupied by a distinctly feminine figure identified as John the Evangelist, based on the painting in Ponte Capriasca. Even in this copy, created over 250 years later, John maintains an unmistakably feminine appearance.

Of particular interest is the fact that numerous texts and apocryphal Gospels recount a certain rivalry, if not outright animosity, between Peter (or Simon the Zealot) and Mary Magdalene.

In the painting, it becomes apparent that the feminine figure might be identified as Mary Magdalene or Mary of Bethany, “the favored one whom Christ kissed on the mouth” (Gospel of Philip). Meanwhile, the man in light clothing with an aggressive posture is Peter, seemingly reaching out with his hand as if to cut the throat of Christ’s favored companion.

Additionally, a mysterious hand armed with a knife appears behind Peter, as though ready to strike...

These and other details strongly suggest that Leonardo da Vinci, as a distinguished member of the Neoplatonic Academy, was deeply versed in the gnostic and apocryphal heritage—hidden from the world until the 1940s with the discovery of the gnostic texts in the caves of Qumran and Nag Hammadi, which are now available to us.

A drawing on cardboard, housed in the National Gallery and also known as "Anna Selbdritt," depicts the Virgin Mary seated on the lap of her mother, Saint Anne. Mary holds the Christ Child in her arms as He blesses the infant John the Baptist. In the center, between two heads, a symbolic gesture of the index finger pointing upward is once again depicted. However, the proportions of the hand are distorted, and the hand appears to originate from Saint Anne herself, who gazes at Mary with an intense and "enigmatic" expression.

It is particularly intriguing to note how this gaze closely resembles the image of John the Baptist as portrayed in Leonardo's famous painting Saint John the Baptist, also displayed at the Louvre.

A few years later, however, Leonardo repainted the scene of Mary and Saint Anne with Jesus, this time without the infant John, who is replaced by a lamb. The symbolic gesture is no longer present. Interestingly, according to the Gospels, it was John who pointed to Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world, not the other way around.

In this painting, the depiction of a simple lamb becomes a precise subliminal message, intended to reaffirm the supremacy of John the Baptist over Christ, as suggested by Mandaean tradition.

In his later years, Leonardo painted John the Baptist again, this time portrayed as Bacchus, in a larger canvas now housed in the Louvre.

In this magnificent painting, alongside the gesture, other symbols of great importance are present: the deer, the bear, and the columbine plant.

The deer symbolizes the aspiration for eternal life, the bear represents cosmological renewal, and the columbine, an androgynous plant like the god Bacchus, signifies the union of the human soul with divine unity.

Even in the painting The Madonna of the Yarnwinder, Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece stolen six years ago and now once again displayed in Scotland, there are elements suggesting hidden symbolic messages.

In this painting, the child holds a cross-shaped staff in his hands, a symbol of the Baptist, while subtly making the ritual gesture with his index finger.

The interpretation of this gesture, obsessively painted by Leonardo and sometimes referred to as "The Finger of God," is believed in light of Mandaean beliefs to symbolize the supremacy of John the Baptist over Christ—almost suggesting that the true Messiah was John, not Jesus.

Such convictions are widely present in Johannite writings, which often emphasize that John, as a descendant of the Levitical line, was destined for the role of Priestly Messiah, while Jesus, as a descendant of David, was seen as the Temporal Messiah. The Gospels frequently describe Jesus as the son of David, and it is no coincidence that He was crucified under the Titulus Crucis inscription "INRI," the Latin initials for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum ("Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews").

This is why, in Mandaean texts such as the Ginza Rabba and particularly the Haran Gawaita, John refers to Jesus, saying:

"Yeshu distorted the words of the light and turned them into darkness; he converted those who were mine and altered all rituals..."

He is thus accused of being the traitor—the false Messiah.

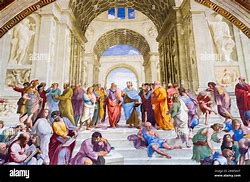

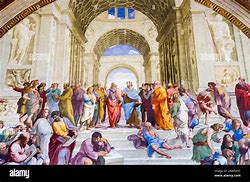

The same symbol appears in the Vatican fresco of the Stanza della Segnatura titled The School of Athens, painted between 1509 and 1510 by Raphael Sanzio.

At the center, in the foreground, we unexpectedly recognize, next to Aristotle, none other than Leonardo da Vinci himself, making the symbolic gesture he obsessively painted.

Raphael Sanzio, too, was among the members of the Florentine Neoplatonic School and thus an initiate.

Research Journey

Exploring the intersections of science and history through independent research.